Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Het zakelijke socialmediaplatform LinkedIn heeft een video van De Correspondent zonder enige waarschuwing verwijderd van ons account. Ook volgers die de video wilden delen, melden dat hun posts worden verwijderd. In de video noemt hoofdredacteur Rob Wijnberg op basis van feiten de Amerikaanse president Donald Trump het grootste gevaar voor de wereld sinds Adolf Hitler.

Het maken van dit verhaal kost tijd en geld. Steun De Correspondent en maak meer verhalen mogelijk voorbij de waan van de dag. Dankzij onze leden kunnen wij verhalen blijven maken voor zoveel mogelijk mensen. Word ook lid!

Zakelijk lid worden is ook mogelijk, dit kan al vanaf 5 medewerkers. Steun ons en vraag direct een zakelijk lidmaatschap aan.

Wil je eerst kennismaken met onze verhalen? Schrijf je dan in voor de proefmail en ontvang een selectie van onze beste verhalen in je inbox.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

De machtige techmiljardairs zijn in de ban van de absurdste toekomstvisioenen, geïnspireerd op oude sciencefiction. Wat blijft er over als je hun theorieën afpelt, vroeg astrofysicus Adam Becker zich af. Zijn conclusie: vooral de sloop van mens en planeet.

Ik wist dat veel techmiljardairs – Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Peter Thiel, dat soort mannen – er even rare als problematische wereldbeelden op nahouden. De een wil Mars koloniseren, de ander wil onsterfelijkheid – al eeuwen typische dromen voor de superrijken. Maar wat ik niet wist, is dat dit pas het begin is van hun fantasieën.

Het maken van dit verhaal kost tijd en geld. Steun De Correspondent en maak meer verhalen mogelijk voorbij de waan van de dag. Dankzij onze leden kunnen wij verhalen blijven maken voor zoveel mogelijk mensen. Word ook lid!

Zakelijk lid worden is ook mogelijk, dit kan al vanaf 5 medewerkers. Steun ons en vraag direct een zakelijk lidmaatschap aan.

Wil je eerst kennismaken met onze verhalen? Schrijf je dan in voor de proefmail en ontvang een selectie van onze beste verhalen in je inbox.

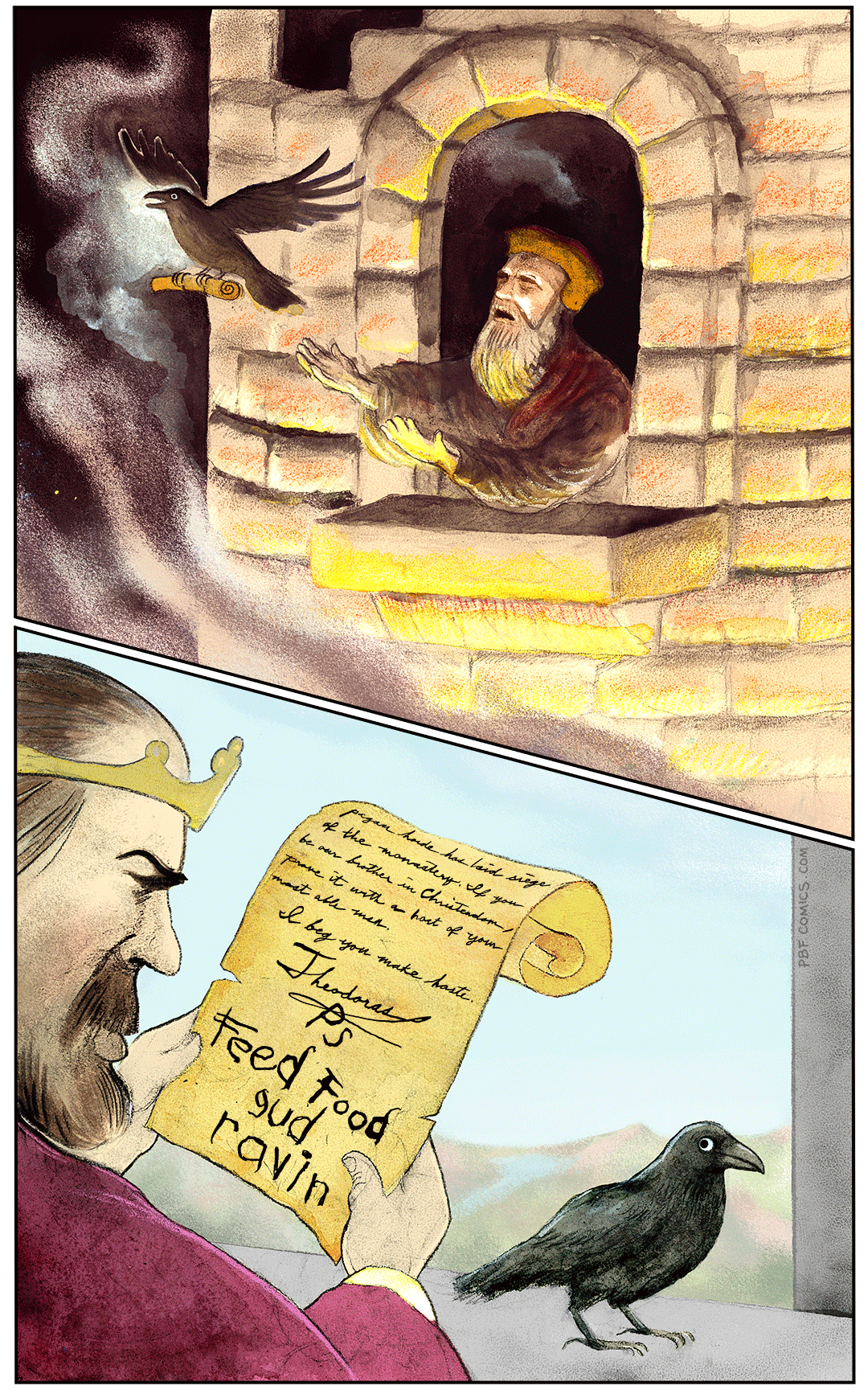

The post The Message appeared first on The Perry Bible Fellowship.